Tips on Finding the Elusive Ship Record

Very frequently, people ask questions about how to find the ship records of their ancestors that came to the United States. Below are five general pointers that I find particularly useful to those that are struggling with finding that elusive ancestor's ship record. The below examples relate to Jewish immigrants but apply equally to those of other backgrounds.

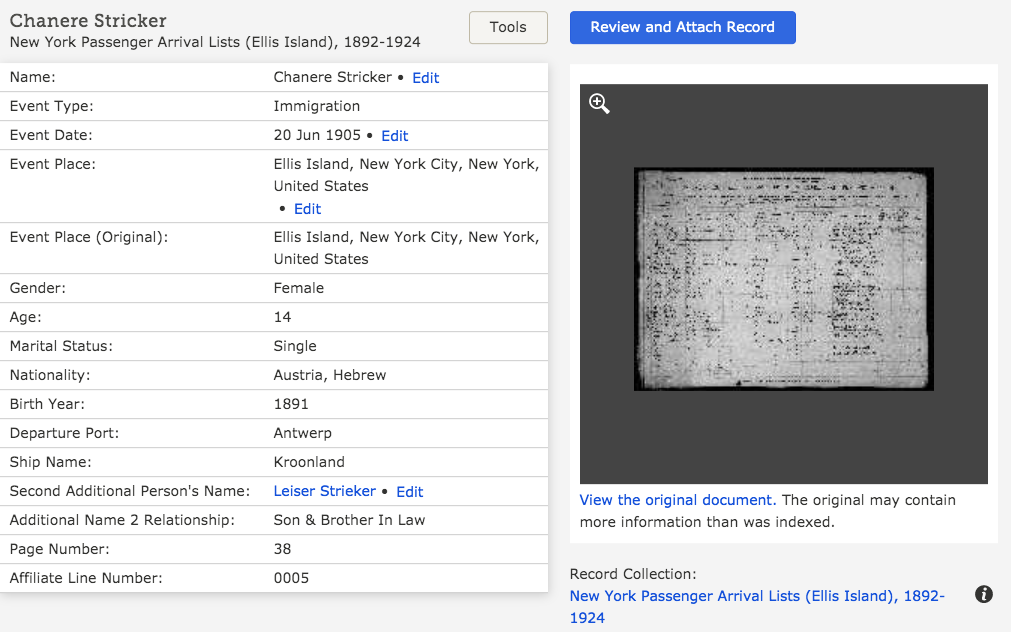

1. FamilySearch.org is a free website that has indexed most US immigration records. FamilySearch actually includes more data than Ancestry.com does in most of its immigration indexes. For example, FamilySearch often shows in its search results the individual to whom the immigrant was traveling upon arrival in the United States, an often times helpful reference point to see whether the match is correct or not. Simply create a free account on FamilySearch and search, and you can filter for immigration records. (Note: this information is also included on MyHeritage's ship record indexes).

2. Names were not changed at Ellis Island (that's correct! see here or here or here, for example). So you can’t simply search a Yiddish-speaking "Harry" or "Sam" and find the match. If your family came from Eastern Europe and you don’t know what a person’s original first name was, you should google common Yiddish names and see which names start with the same first letter as the individual used in the US; and try different ones. If your family came from Europe later into the twentieth century, look up the origin country’s equivalents of the English name, and search for that too. For example, Harry from Poland could have been Hirsch or Herschel or Chaim in Yiddish, while a later immigrant could have been Henryk.

3. Don’t be a stickler for spelling. Names were altered in the US to Americanize pronunciation. Also, immigrants' names at different ports were transcribed differently. For instance, if families traveled through Hamburg or England to the US, the spelling of their names could have differed. For example, an immigrant through Hamburg might have "sch" used in a name while an immigrant through England might have "sh" instead. Similar patterns might emerge for the use of w or v, or the use of letters such as ö or ü. For instance, an American with the surname Levenstein could have immigrated through Hamburg as Löwenstein.

4. Use the JewishGen Communities Database to check the name of a town and what country it was located in at various times. For example, an Austrian immigrant from Lemberg in 1900 could be the brother of a Polish immigrant from Lwów in 1930, who could be uncles of a Soviet/Ukrainian immigrant from L'viv in the 1970s. (Hint: they're all the same town!)

|

Excerpt of the JewishGen Locality Page for L'viv Ukraine |

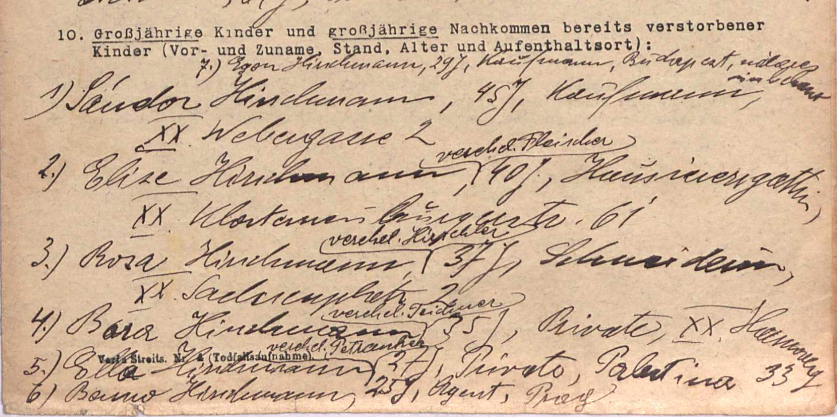

5. Use wildcards (such as an asterisk) for missing letters to refine searches. On both Ancestry and FamilySearch, you can use the asterisk to replace letters and find more records (although not on MyHeritage). For instance, if someone’s surname was Snyder in the US, searching S*n*der* will catch records for Snyder, Schneider, Schneiderman, etc. Or to use the above example, L*nstein would capture the surname Levenstein or Löwenstein. FamilySearch is very flexible with this, but Ancestry is a little stricter (requiring three letters and a starting or finishing letter). Ancestry also has a question mark that can be used to leave one letter blank. This is very useful for vowels that can be transcribed improperly (for example, searching for C?h?n will catch results for Cohen, Cahen and Cahan).

These are some introductory strategies which I hope will help you in your search. Good luck!

Enjoyed this post? Sign up here to receive email updates for when new posts are available.

Comments

Post a Comment